Yokai are a category of supernatural monsters from Japanese folklore. They encompass a wide range of beings, from mischievous spirits to fearsome monsters, and are often associated with strange phenomena and unexplained events. In the late 1960s, Daiei Studios created a trilogy of films with this theme, managing to make each one distinct from the others, much like the yokai themselves.

Yokai Monsters: 100 Monsters (original title: Yōkai Hyaku Monogatari, literally One Hundred Yōkai Tales), released in 1968, is the first in the trilogy. Directed by Kimiyoshi Yasuda (better known for his work on the Zatoichi series), the film combines Edo-period ghost storytelling traditions with practical effects and folkloric imagery, weaving a moralistic parable into a tapestry of the supernatural.

Although it often suffers from tonal inconsistency and dated effects, 100 Monsters holds historical and cultural importance as an early cinematic attempt to visualize Japan’s rich folkloric tradition of yokai through live-action. The film bridges classical kaidan (ghost story) aesthetics with the more commercial jidaigeki (period drama) and tokusatsu (live-action films or tv shows that make heavy use of special effects) traditions of postwar Japanese cinema.

At its core, 100 Monsters is a morality tale disguised as a ghost story. A greedy land developer and a corrupt magistrate team up to destroy a tenement and sacred shrine to build a brothel, disregarding both the law and spiritual taboos. Their actions include disrupting a traditional hyaku monogatari (one hundred tales) ghost-story gathering, in which participants extinguish one candle for every story told.

The narrative progresses slowly, focusing more on human greed, oppression, and sacrilege than on the yokai themselves. In fact, supernatural events are mostly confined to the third act, creating a stark contrast between the mundane and the uncanny. The film uses yokai as agents of karmic justice, as the eventual supernatural vengeance is not just a horror spectacle but a cosmic rebalancing against injustice.

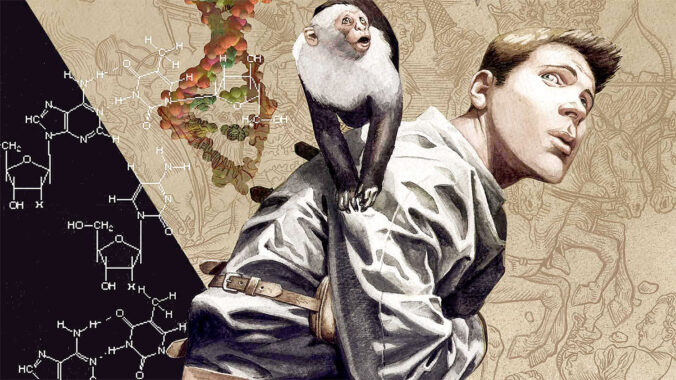

The effects, while primitive by modern standards, rely on a mix of suitmation (actors in costumes), puppetry, and practical trickery. The yokai designs are based on classical emaki (picture scrolls), particularly those by Toriyama Sekien. This dedication to traditional imagery gives the creatures a unique cultural authenticity rarely seen in Western monster films of the same era. Among the yokai we see the classics kasa-obake (the hopping umbrella ghost), rokurokubi (the woman with a stretching neck), and noppera-bō (the faceless ghost).

Akira Ifukube (best known for scoring the first Godzilla) provides a subdued yet ominous score that complements the restrained pace. The use of silence and ambient sound also enhances the tension, particularly in scenes leading up to the yokai appearances.

However, the film struggles to maintain a consistent tone. The slow buildup and excessive focus on corrupt landlords and local politics, while thematically relevant, may test viewers’ patience. This makes the final act, where yokai finally appear, feel both rewarding and too little, too late.

Yokai Monsters: Spook Warfare (original title: Yōkai Daisensō, literally The Great Yokai War), also released in 1968, is the second entry in Daiei Studios’ yokai trilogy. Directed by Yoshiyuki Kuroda and released just months after 100 Monsters, this sequel pivots dramatically in tone, structure, and style. Where 100 Monsters was a slow-burning, moralistic kaidan (ghost story) steeped in atmospheric dread and karmic retribution, Spook Warfare gleefully transforms the yokai into active protagonists in a supernatural adventure. The result is a surreal genre mashup: part horror, part tokusatsu action, part children’s fantasy, and entirely sui generis. While it lacks the moral depth and thematic gravity of its predecessor, Spook Warfare succeeds through sheer visual invention and its unprecedented commitment to yokai spectacle. It’s campy, chaotic, and utterly unique.

The film opens in ancient Babylon, where a demon named Daimon (styled after a Western vampire or necromancer) is awakened from a long slumber. After arriving in feudal Japan via a possessed statue, Daimon promptly kills a magistrate and assumes his form, ruling the town with dark magic and feeding on human blood. The local yokai detect the foreign presence and begin to mobilize in defense of their homeland.

This east-vs-west supernatural conflict propels the plot. Unlike the minimal yokai presence in 100 Monsters, here the yokai are fully active agents with personalities, motivations, and even battle strategies. They unite, squabble, and fight like a supernatural resistance force.

But Spook Warfare takes a sharp turn toward the whimsical. While still set in a historical period, the film eschews the moody austerity of 100 Monsters for a playful, even goofy tone. The yokai are no longer eerie omens of spiritual judgment, they’re now folk heroes. This tonal shift broadens the film’s appeal to younger audiences while also reflecting the growing popularity of yokai in children’s media, particularly through the work of manga artist Shigeru Mizuki. This comes at the cost of emotional depth. Themes like cultural identity, tradition, and collective resistance are hinted at but rarely explored in detail. The film is more about fun than fear, more spectacle than story.

A potentially deeper layer lies in the framing of the villain. Daimon is explicitly foreign: Babylonian, vampiric, with Western-style robes and magic. His invasion of Japan and possession of a magistrate could be read as an allegory for cultural intrusion, colonialism, or postwar Westernization. The yokai’s defense of their native land might represent a kind of folkloric nationalism: Japan’s traditional spirits defending cultural identity against a foreign evil. Yet the film doesn’t explore this with any real nuance. It’s more a structural motif than a fully realized allegory.

Yokai Monsters: Along with Ghosts (original title: Tōkaidō Obake Dōchū, literally The Haunted Journey Along Tōkaidō), released in 1969, is the third and final entry in Daiei Studios’ trilogy. Co-directed by Yoshiyuki Kuroda (Spook Warfare) and Kimiyoshi Yasuda (100 Monsters), the film returns to a more somber, morally grounded tone reminiscent of the first film, diverging sharply from the colorful playfulness of Spook Warfare. It is less of a yokai showcase and more of a traditional jidaigeki (period drama) with supernatural overtones.

This fusion of ghostly folklore with a grim tale of vengeance and redemption makes Along with Ghosts the most narratively serious and dramatically intense of the trilogy, but also the least fantastical. While its yokai elements are used sparingly, they remain thematically integral, acting as both symbolic and literal agents of justice.

The film opens with a treacherous act: an old man witnesses the murder of a courier before he can deliver crucial legal documents meant to stop a criminal gang, and then is he is also murdered. His young granddaughter, Miyo, becomes the target of the villains, and the film follows her perilous journey along the old Tōkaidō Road as she seeks safety and justice. A wandering swordsman with a mysterious past, closer to a ronin archetype than a folkloric figure, comes to her aid.

The yokai in this entry are peripheral but potent. Unlike in Spook Warfare, where they’re protagonists, or in 100 Monsters, where they’re manifestations of spiritual retribution, here they are ghostly echoes that haunt the edges of a brutal human world. Their appearances are minimal and atmospheric, usually connected to locations desecrated by violence or injustice.

The narrative structure is more conventional: a straight revenge-pursuit drama with clear moral stakes punctuated by moments of supernatural intervention. The emotional center is Miyo, whose innocence and suffering lend the film its gravitas. As with the previous two films, Along with Ghosts frames its story around the consequences of moral corruption. The film is a condemnation of human cruelty, particularly that inflicted upon the vulnerable, like women, children, and the elderly. The yokai are not the cause of fear, they are the consequence of wrongdoing.

Stylistically, Along with Ghosts is darker, more violent, and less fantastical than its predecessors. The directors employ a muted color palette and minimal musical scoring to create an oppressive and eerie atmosphere. Much of the film takes place in forests, graveyards, and rural roads, giving it the feel of a ghostly travelogue through haunted Japan.

The adorable child actress playing Miyo (Masami Furukido) delivers a notably moving performance. Her fear, tenacity, and innocence are all convincingly rendered. The ronin protector (Kôjirô Hongô), while archetypal, provides a stoic counterbalance and channels the genre conventions of the silent defender. The villains, as in many jidaigeki of the era, are unambiguously wicked, cowardly, greedy, and contemptuous of tradition. Their downfall, precipitated by ghostly visitations, feels less like plot convenience and more like the fulfillment of cosmic justice.

So 100 Monsters was a folkloric sermon inside a kaidan (ghost story), Spook Warfare was a tokusatsu yokai adventure that played like a Saturday morning cartoon, and Along with Ghosts was a revenge road drama with yokai as haunting punctuation marks. In this sense, the trilogy moves full circle: from dread, to spectacle, back to dread but now filtered through tragedy.