There is a particular kind of American fantasy that rolls into town on squeaky wheels: a carnival, a circus, a sideshow. It promises wonder, then quietly reorders your soul. Charles G. Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao (1935) drops a surreal menagerie into a dusty Arizona town. Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962) delivers a traveling nightmare to a small town in Illinois, baiting people with the one thing they want most.

The enduring appeal of these fantasies becomes even more apparent when examining their film adaptations, which reveal as much about Hollywood as about the books themselves. George Pal’s 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964) turns Finney’s sharp, episodic satire into a warm(ish) fantasy Western built around a tour-de-force gimmick performance, while Jack Clayton’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) becomes a beautifully moody, famously troubled production even though Bradbury wrote the screenplay himself.

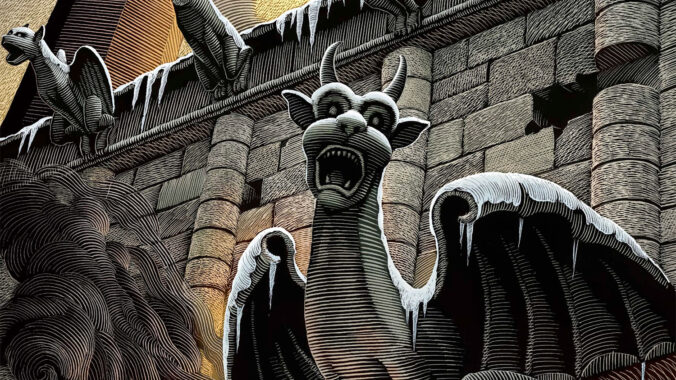

Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao is compact, strange, and structured like a chain of encounters. The circus arrives in Abalone, Arizona, and townspeople wander through attractions that feel less like entertainment than moral or existential stress tests. The creatures aren’t just monsters, they are arguments in costume. The book even caps itself with an appendix-style catalogue that snarks, clarifies, and undercuts, as if the novel can’t resist heckling its own myth-making.

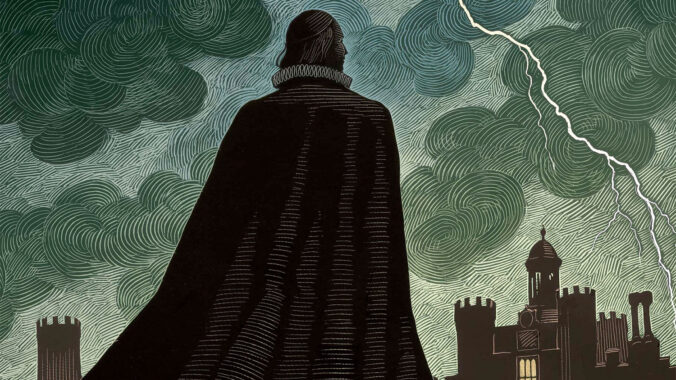

Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes is not episodic but a continuous, intensifying narrative centered on Jim Nightshade and Will Halloway. They confront a carnival led by Mr. Dark, who exploits longings, especially fear of aging, regret, and loneliness.

Where Finney’s prose often feels like a clever blade, Bradbury’s feels like autumn air. It’s lyrical, nostalgic, and then suddenly freezing. Even the premise carries a thematic engine: the carnival doesn’t merely frighten you, it customizes itself to whatever soft spot you refuse to admit you have.

Both novels use “the show” as a delivery system for temptation and revelation. But Finney’s circus is a surreal civic audit (the town is measured, found wanting, and left with consequences that feel harshly cosmic), while Bradbury’s carnival is intimate and psychological (it’s about the moment childhood ends, and the first time you realize adults are just kids with heavier masks).

George Pal’s 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964) is explicitly based on Finney’s novel, but it only follows it in the loosest sense: it keeps the basic situation (a magical circus transforms a town) while changing and simplifying much of what makes the book so wonderfully abrasive. The most obvious pivot is the movie’s central hook: Tony Randall plays Dr. Lao and a roster of other figures (the faces), turning the story into a showcase of performance and transformation. The film also adds a more conventional, external conflict, an outright land/railroad-related swindle subplot, to give the town a plot in the Hollywood sense, not just a series of encounters. And then there’s the craft: the movie is famous for its makeup and effects. Makeup artist William Tuttle received a special Academy Award for this work, even though makeup was not an official Oscar category at that time. But the adaptation also drags a cultural problem into the spotlight. The film’s version of Dr. Lao (a Chinese character played by a non-Asian actor) sits in the long, ugly history of Hollywood “yellowface”, which changes the flavor of the story in a way the book doesn’t require.

On paper, the Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) adaptation sounds like the dream scenario: Bradbury wrote the screenplay for the film version of his own novel. In practice, it became a case study in how films get transformed into a different creature. Both AFI’s production history and widely repeated accounts point to the same core reality. The movie had a turbulent development and a troubled production, with studio intervention after test screenings. After test screenings, Disney sidelined the director, replaced the editorial and music choices, and undertook extensive changes. And yet, when the film works, it works because it honors Bradbury’s mood: the autumnal dread, the hush before the scream, the sense that the fun of a carnival is just a mask with something hungry behind it. The casting helps: Jonathan Pryce’s Mr. Dark is an elegant menace, and Jason Robards brings gravity to the father figure who, in Bradbury, functions as the story’s moral counterweight.

The contrast between novel and film is especially sharp in Pal’s movie, which treats Dr. Lao as a premise rather than a structure. The novel’s episodic cruelty and meta-textual bite (including that catalogue appendix) are difficult to translate directly, so the film makes a pragmatic decision: give the audience a throughline (a town conflict) and a spectacle engine (Randall’s transformations).

Bradbury’s novel is already cinematic in the way it builds dread. But the film version ends up fighting two impulses: to preserve Bradbury’s lyric melancholy and moral seriousness, and to package the darkness in a Disney-friendly vessel. The production history matters here. It explains why many viewers report a movie with moments of genuine power, but with seams visible from reworking and reshaping.

Taken together, these two carnival stories map a fascinating spectrum of American fantasy, both on the page and on the screen. Finney gives you a surreal, satirical circus that exposes a town’s smallness with almost mythic indifference. Bradbury gives you a dark fairytale of adolescence, in which evil is less a monster than a transaction. “I’ll give you what you want, and take what you are.” And their adaptations remind you of a final truth: when Hollywood buys a ticket to a strange show, it often tries to rewrite the act. Sometimes that produces a charming new performance (7 Faces of Dr. Lao). Sometimes it produces a beautiful, bruised artifact that still smells like autumn lightning (Something Wicked This Way Comes).