Well, Wasteland 3 is not exactly an old CRPG (it was launched in 2020), and I’m not actually replaying it (because I never had the opportunity to play it before), but after Wasteland 2 it was an obvious choice for this series anyway.

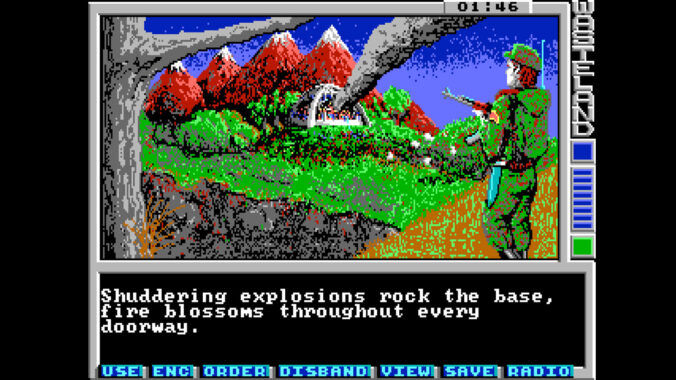

The Wasteland franchise has always carried the weight of history. The original Wasteland (1988) laid the groundwork for post-apocalyptic RPGs and directly inspired the Fallout series. Decades later, Wasteland 2 (2014) revived the series with a modernized isometric format, featuring heavy text and a branching narrative. Wasteland 3 (2020), developed by inXile Entertainment, continues that revival but shifts the setting from the deserts of Arizona to the frozen wastelands of Colorado. This new location gives the franchise fresh thematic ground: coldness, scarcity, and survival under a tyrant’s shadow, while still keeping the Rangers as the moral (or amoral) focal point.

The Rangers once again act as the thin line between order and chaos, but instead of rebuilding the Southwest, they’re drawn into the power struggles of Colorado. The Patriarch, a strongman leader, asks them to capture his rebel children and stabilize his rule in exchange for aid to Arizona. This premise ties naturally into the ongoing Wasteland storyline: Rangers as outsiders forced to broker deals between factions, never truly at home, never entirely in control. It continues the franchise’s tradition of examining the tension between idealism and pragmatism in post-nuclear America.

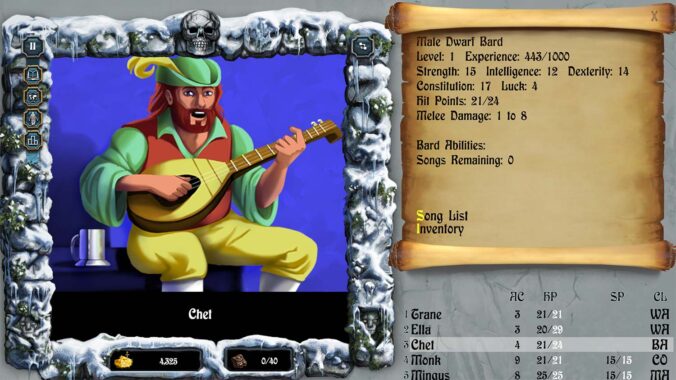

Compared to the previous title in the series, Wasteland 3 brings several improvements. The turn-based tactical system feels tighter, with clearer action-point management, improved cover mechanics, and more dynamic execution. Full voice acting elevates the narrative and adds personality to factions and NPCs, reducing the fatigue of reading walls of text. Inventory and squad management are far more intuitive than in Wasteland 2, making long play sessions smoother. It’s not revolutionary, but it feels more confident and accessible without losing complexity.

That said, Wasteland 3 is no stranger to technical hiccups. At launch, and even after multiple patches, players reported crashes, quest-breaking bugs, and odd AI behavior. While many of these issues were gradually addressed, some persist even years later (and I experienced a few of them). The game is undeniably playable and fun, but the lingering rough edges betray its mid-budget production and occasionally undermine immersion.

The main story is one of the game’s strengths. Choices ripple through the world: siding with or against factions, deciding the fate of the Patriarch’s family, and ultimately determining what kind of Colorado will emerge. These ramifications create multiple endings that feel meaningfully different, a hallmark of the franchise and a significant reason for replayability. I actually played it twice, once with the Rangers truthfully on the Patriarch’s side and then with the Rangers subtly scheming against him and taking him down in the end.

Some quests shine with moral depth, while others feel rushed or unbalanced. Example of a good quest: Call to Action. This mission epitomizes what Wasteland 3 can do well. You face a moral decision where either path is rewarding, though in different ways. Instead of punishing creativity or diplomacy, the quest recognizes multiple solutions, making the player feel that their role-play matters. Example of a bad quest: Disappeared. The setup, choosing between killing one group of people, killing the other, or negotiating peace, seems promising. Yet the peaceful solution yields no rewards at all, making it ironically the least attractive option. This undermines the spirit of choice-driven gameplay and encourages players to resort to violence, even when their character wouldn’t necessarily choose to do so.

The Refugees faction encapsulates the game’s ambivalence about moral versus mechanical incentives. In theory, Rangers are protectors of the downtrodden, so siding with refugees should feel natural. In practice, however, it’s punishing: helping them brings no material rewards, damages relationships with other factions, and can even result in the refugees attacking you in the end. While this may be thematically intentional, showing the cost of altruism in a broken world, it risks alienating players who feel their compassion is being punished without narrative justification.

The DLC The Battle of Steeltown is a solid addition. It expands the world organically, with new moral quandaries and a fresh industrial backdrop. Its themes of labor, oppression, and survival connect smoothly to the main plot, making it feel like a natural extension. But the DLC Cult of the Holy Detonation is much less successful. It’s disconnected from the main story and relies heavily on gimmicky mechanics, such as ever-spawning enemies. Instead of being more challenging, this design choice makes encounters tedious and repetitive, draining the fun rather than enhancing it.

Wasteland 3 is a worthy successor that strikes a balance between accessibility and depth. Its narrative ambition, colorful factions, and branching paths make it compelling, even if not every quest lives up to the promise. Bugs and some frustrating quest designs hold it back, and the uneven DLCs show both the highs and lows of inXile’s experimentation. Wasteland 3 may stumble at times, but it delivers a memorable, choice-rich RPG that keeps the franchise alive and thriving. It’s a flawed gem, but a gem nonetheless.