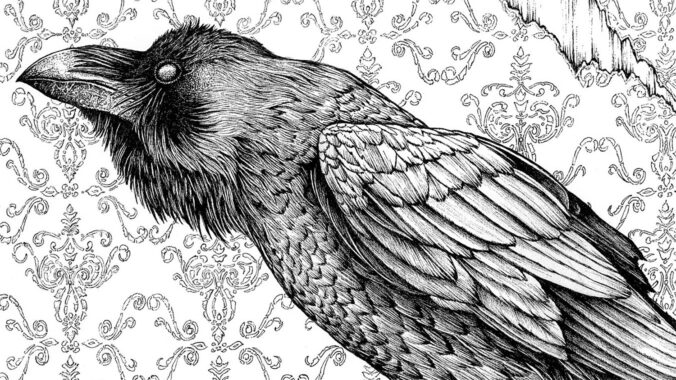

In one of my weekend trips to Philadelphia, I went to the Parkway Central Library to visit Grip. If you are a reader of Charles Dickens or Edgar Allan Poe you may know a thing or two about him.

In 1941, Charles Dickens published the novel Barnaby Rudge, which had been serialized in the same year in his own weekly periodical Master Humphrey’s Clock. As a companion to the title character, Dickens added a large and talkative raven called Grip. His idea, expressed in a letter to a friend, was to make the bird “immeasurably more knowing” than the protagonist. Grip is often described in the book with almost human attributes, like when he is listening to a conversation “with a polite attention and a most extraordinary appearance of comprehending every word, to all they had said up to this point; turning his head from one to the other, as if his office were to judge between them, and it were of the very last importance that he should not lose a word”. One of my favorite bits offers an amusing account of his movements: “he fluttered to the floor, and went to Barnaby — not in a hop, or walk, or run, but in a pace like that of a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles”.

Dickens explains in the preface to Barnaby Rudge that Grip was a composite of two ravens that he had owned. The first one lived in the stable and terrorized the dog, often stealing his dinner. Unfortunately, when the stable was being painted, he also decided to steal and eat the paint. He died of lead poisoning. Hearing of this sad loss, a friend sent another raven to Dickens, this one “older and more gifted”. The second bird also made the stable his home but habitually explored a larger area. “Once, I met him unexpectedly, about half-a-mile from my house, walking down the middle of a public street, attended by a pretty large crowd, and spontaneously exhibiting the whole of his accomplishments.” He died after three years or so, and since then Dickens was, to use his own word, ravenless.

Both ravens were called Grip, so it’s unclear which one Dickens decided to have stuffed and mounted in a somewhat grandiose display box. Saved for posterity in taxidermic splendor, Grip was auctioned after the author’s death and changed hands a few times before taking residence in Philadelphia.

It was a cold Saturday morning when I took the elevator to the almost empty third floor of the Parkway Central Library. The security guard was getting ready to eat his breakfast burrito and ushered me in with a nod of this head. I traveled the L-shaped corridor of the Rare Books Department, surrounded by old volumes locked behind the glass doors and observed by a few solemn statues: two versions of Johannes Gutenberg, with and without his hat, and a magnificently bearded Charles Dickens at age fifty-seven. Around the corner, at the end of the hall, there he was, Grip, surprisingly large and ominously black. The bird is, indeed, impressive, and suggests, even in death, the imposing presence it may have had in life.

Grip is in an elaborate glass and wood box, which was placed inside another glass box. This arrangement creates a system of unwanted reflections, frustrating to casual photographers. The kind librarian who was on early duty that day saw me struggling to get a good angle and, unable to help me solve that particular problem, decided to offer me something else. She unlocked the Elkins Room and invited me to spend some time there.

William McIntire Elkins was a collector of rare books with a particular predilection for Dickens. He bequeathed his collection to the Free Library of Philadelphia, and when he died in 1947 his whole reading room, complete with books and shelves, tapestries and chandeliers, and even a fireplace, was moved to the Parkway Central Library. One of the most precious objects in this beautiful personal library is the writing table used by Charles Dickens from 1837 up to his death in 1870. There it was, small but elegant. On the worn surface, as if to leave no doubt who it had belonged to, the initials C.D. roughly chiseled by the author himself.

But back to Grip. I don’t think I have ever seen a raven that big, stuffed or not. It’s fun to imagine how meeting a live bird of that size, moving and talking, would have been an impressive experience. It captivated Dickens’s imagination and, via the printed page, reached another author on the other side of the ocean, Edgar Allan Poe.

Grip may not be the direct inspiration for The Raven, one of the most famous poems in the English language (and other languages as well, translated to French by Charles Baudelaire and by Stéphane Mallarmé, and to Portuguese by by Machado de Assis and by Fernando Pessoa, just to mention a few respected names) but it certainly had some influence over Edgar Allan Poe.

Poe was not only familiar with Barnaby Rudge but also wrote a full review of the book for Graham’s Magazine in 1842. “The raven, too, intensely amusing as it is, might have been made, more than we now see it, a portion of the conception of the fantastic Barnaby.” Apparently, Poe would have preferred a stronger connection between Grip and Barnaby. “Each might have differed remarkably from the other. Yet between them there might have been wrought an analogical resemblance, and, although each might have existed apart, they might have formed together a whole which would have been imperfect in the absence of either.” Poe’s The Raven was published in 1845.

At certain point in Barnaby Rudge, two characters are talking about the raven. One of them asks “What was that? Him tapping at the door?”, while the other responds “It was in the street, I think. Hark! Yes. There again! ‘Tis some one knocking softly at the shutter.” And in the first few verses of The Raven we can find “While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, / As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. / ’Tis some visitor, I muttered, tapping at my chamber door— / Only this and nothing more.” Inspiration? Coincidence? Unrelated?

The Raven is one of the most celebrated literary pieces in history, and inspired all kinds of homages, from Freddie Mercury singing Nevermore to Bart Simpson transmuted into a raven in Treehouse of Horror, and not forgetting, of course, the Baltimore Ravens, Super Bowl champions of 2000 and 2012. One of my favorite weird connections is Paul Gauguin’s painting Nevermore, a reclined female nude with a raven in the background next to the word “nevermore”. For some obscure reason, Gauguin denied the obvious association with Poe’s poem and claimed he meant the raven to be just a symbol for the devil. Curiously, the first time Grip appears in Barnaby Rudge he seems to enjoy repeating “I’m a devil, I’m a devil, I’m a devil. Hurrah!”

Dickens fan, or Poe fan, or just curious to see an impressively large stuffed raven? Go to Philadelphia and visit Grip. He’s a devil.