I’ve recently had the chance to see two movies I had never seen, Judge Dredd (Danny Cannon, 1995) and Dredd (Pete Travis, 2012). They are both adaptations of the comic strip Judge Dredd, but they differ significantly from each other.

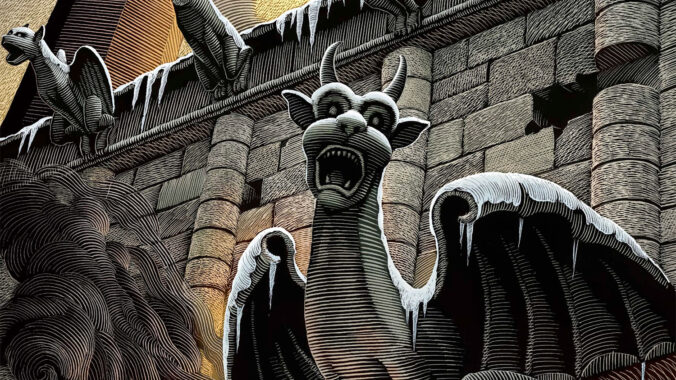

Judge Dredd first appeared in 1977 in 2000 AD, a British weekly anthology comic, created by writer John Wagner and artist Carlos Ezquerra. The strip was a reaction against both American superhero excess and the bleak prospects of late-20th-century urban life. The setting, Mega-City One, was a sprawling dystopian metropolis stretching along the American eastern seaboard, plagued by crime, unemployment, and social decay.

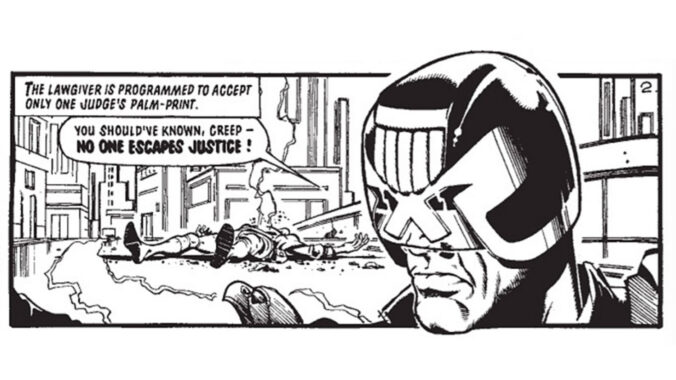

Dredd himself was conceived as the ultimate law enforcer: judge, jury, and executioner rolled into one. He wore a militaristic uniform with oversized pauldrons, hid his face behind a helmet, and spoke in terse, authoritarian commands. The character was never meant to be a hero in the traditional sense. Instead, the comics satirized authoritarianism, policing, and state power. The world of Judge Dredd is one in which the law is absolute but also absurd, reflecting anxieties about fascism, militarization, and the erosion of civil liberties.

A key point is that Wagner and Ezquerra didn’t present Dredd as purely admirable or purely villainous. He was both protector and oppressor, embodying the contradictions of a society that sacrifices freedom for security. This ambivalence made the strip unique: readers could cheer for Dredd’s brutal efficiency one moment and recoil at his inhumanity the next.

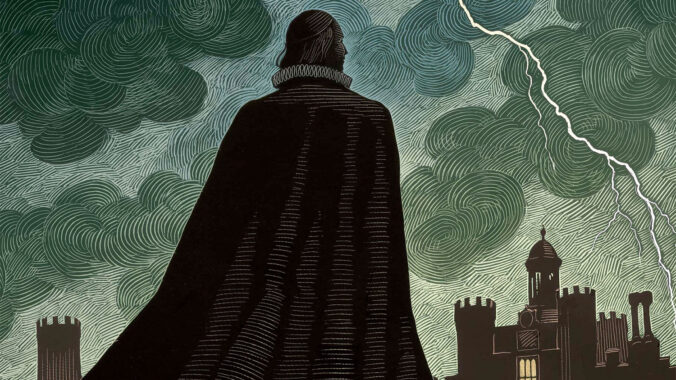

The first significant attempt to bring the character to the screen was the 1995 film, Judge Dredd, directed by Danny Cannon and starring Sylvester Stallone. Hollywood, however, took significant liberties, as it often does. The movie largely abandoned the satirical edge of the comics in favor of a more conventional action hero flick.

Two controversial choices defined this adaptation. First, Stallone removed the helmet for much of the film, undermining one of the character’s essential traits. In the comics, Dredd’s facelessness symbolizes his role as an impersonal instrument of the law. By showing his face, the movie personalized him, trying to turn him into a sympathetic action hero. And then there’s the tone shift. Instead of a biting critique of authoritarian justice, the film leaned on big explosions and campy humor. Rob Schneider’s annoying comic-relief sidekick, created just for the movie, epitomized this tonal mismatch.

The socio-political undertones were diluted. The movie glossed over issues like corruption and cloning, instead favoring an individualistic narrative where Stallone’s Dredd proves his innocence and defeats his evil twin. Rather than questioning the legitimacy of a justice system where one man can sentence citizens on the spot, the film framed Dredd as a misunderstood hero whose authoritarian streak was simply misapplied by others.

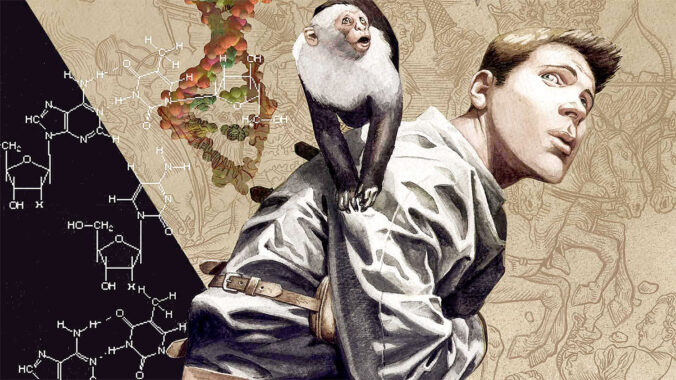

This 1995 version attempted to graft the DNA of Judge Dredd onto the template of a mid-90s blockbuster, featuring big sets, one-liners, and uncritical thinking. The satire and ambiguity of the source material were sacrificed in favor of marketable heroics.

Seventeen years later, Pete Travis’s Dredd, with Karl Urban in the title role, corrected many of its predecessor’s missteps. Urban kept the helmet on throughout, preserving the character’s anonymity and symbolism. The tone was stripped down, brutal, and unflinching, definitely closer to the original grim satire.

The film centers on a single day in Mega-City One, with Dredd and rookie Judge Anderson (this character exists in the comics, but is far from being a rookie) trapped in a mega-block under siege by a drug lord, Ma-Ma. The plot is minimalist, almost claustrophobic, but it highlights key elements of the Dredd mythos.

It’s about the system, not the man. Dredd is not a maverick but an avatar of institutional justice. He doesn’t question the system, he enforces it ruthlessly. His humanity is glimpsed only in subtle ways, primarily through his mentorship of Anderson.

Violence is part of the routine. The film portrays violence with a grim realism. The saturation of slow-motion drug sequences contrasts with Dredd’s mechanical efficiency, underscoring the dehumanizing effects of both crime and policing.

There’s always socio-political commentary. While not overtly satirical, the film critiques a society where entire populations are warehoused in high-rise blocks, policed by authoritarian judges. Anderson’s psychic empathy provides a faint counterweight, reminding viewers that the Judges’ system is ultimately inhuman.

Unlike the 1995 movie, Dredd doesn’t try to make its protagonist lovable. He is the law, nothing more, nothing less. The world here is bleak but consistent: when society collapses, authoritarianism fills the vacuum, but at the cost of individuality and compassion.

I found it interesting to compare specific details in the two adaptations, such as Dredd’s uniform and the depictions of Mega-City One. Stalone wears what appears to be a spandex or Lycra bodysuit, which is remarkably close to what we see in the comics. However, on screen, the costumes look theatrical, flashy, and even campy. Instead of intimidating authoritarian uniforms, they read like superhero cosplay. Urban wears leather and Kevlar-style armor, designed to resemble real-world riot gear combined with tactical SWAT outfits. They kept the helmet, badge, shoulder armor, and overall silhouette, but toned down the bright colors and cartoon exaggerations. Boots and gloves are black, the eagle is muted bronze instead of blaring gold, and the armor looks worn and functional. Not comic-accurate in color or extravagance, but they’re far more convincing in a live-action dystopia. We see the same contrast with the environment. The 1995 Mega-City One is highly futuristic, neon-lit, vertical, like Blade Runner on steroids. Numerous CGI cityscapes, flying vehicles, and giant billboards. It looks like an over-designed movie set rather than a chaotic, lived-in society. The 2012 Mega-City One is a grittier, more grounded interpretation. From afar, it appears as a sprawl of crumbling modern cities, with mega-blocks rising like concrete fortresses amid a sea of urban decay. On the ground, it resembles Detroit or Baltimore with added dystopian rot: graffiti, gang-ruled projects, bleak streets. This nails the tone of Mega-City One as a decayed, crime-ridden society on the brink of collapse.

In conclusion, the 1995 movie incorporates some authentic details (clone origin, Rico, Fargo, Mega-City One, Cursed Earth), but reshapes them into a Hollywood-friendly narrative: the wrongly accused hero, the evil twin, the wise mentor, and the comic-relief sidekick. The comics were far more satirical, cynical, and episodic, whereas the movie attempted to mold Dredd into the conventional blockbuster protagonist. The 2012 Dredd doesn’t try to adapt any single classic storyline, instead it condenses the world’s essence into a tight, brutal scenario. It’s more faithful in spirit than the 1995 film because it retains the helmet, the authoritarian tone, and the oppressive city, but it strips away the comic’s satirical absurdity in favor of realism.