I’ve recently bingewatched the many iterations of Lost in Space. The “castaway as hero” idea is surprisingly adaptable. It has been marooned on islands, stranded on planets, and even hurled across galaxies. As a concept, it all started with one resourceful guy: Robinson Crusoe and his tale of survival that kicked off a whole genre, sparked imitators and adaptations, and eventually landed an entire family Lost in Space.

In 1719, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe hit the shelves, changing the literary world forever. Possibly inspired by the true story of Alexander Selkirk, a marooned Scottish sailor who survived alone on an island for over four years, Defoe created a character that wasn’t just about survival. He was about resilience, ingenuity, and conquering the wilderness. Crusoe embodied the everyman, facing an unknown world with only his wits and some salvaged tools from his shipwreck. Robinson Crusoe became a huge hit, inspiring readers with its themes of self-reliance and adventure. The novel’s success wasn’t just due to its gripping story but also to Defoe’s new, realistic style that made readers feel like they were living each harrowing day alongside Crusoe.

But let’s not forget that Crusoe, by our contemporary standards, was not such a good guy. All that resilience, self-reliance, and determination were supported by his contemporary belief in European superiority, a mindset that defined much of the colonial age. When his shipwreck occurs, he’s en route to buy slaves, demonstrating his view of other people as property. Later, his treatment of Friday, the native man he rescues on the island, also reflects this perspective. Instead of asking for his name, Crusoe just names him “Friday” and establishes himself as “Master”, reinforcing the hierarchy typical of colonial relationships. While Crusoe teaches Friday his language and customs, he doesn’t treat him as an equal. Instead, he sees himself as “civilizing” Friday, which reflects a distinctly European, colonial view of the world and its people. Despite this (or perhaps because of this), Robinson Crusoe resonated widely with readers, not just as a tale of survival, but as a story that expressed Europe’s growing fascination with exploration and domination.

With Robinson Crusoe‘s massive popularity, writers rushed to create similar tales of isolation and survival in hostile environments. Thus was born the “Robinsonade”, a genre that echoed Crusoe’s trials, only with new settings, characters, and scenarios. Robinsonades often share certain characteristics: a protagonist isolated in a hostile or unfamiliar environment and forced to rely on ingenuity to survive, themes of self-discovery, and the idea of re-civilizing oneself while taming the wild around them.

Some notable examples include The Coral Island (1858), by R.M. Ballantyne, where three boys are stranded on a Polynesian island, and Lord of the Flies (1954), by William Golding, which turns the Robinsonade on its head by showing kids devolving into savagery rather than embracing civility. Robinsonades captivated readers by making them ask “What would I do in that situation?”.

If Robinson Crusoe did his thing solo, The Swiss Family Robinson (1812), by Johann David Wyss, took a family of castaways and set them loose on an exotic island. Here, we get the full family adventure, complete with domestic disputes, moral lessons, and an endless supply of miraculously useful shipwrecked supplies. The story follows a pastor, his wife, and their children as they shipwreck on an uninhabited island. Together, they build a treehouse, tame wild animals, and create a self-sustaining mini-society, all while keeping a spirit of togetherness and moral fortitude. Even as a kid, I found that book extremely boring. But in its time the novel became one of the most popular Robinsonades, particularly for children. It made the idea of surviving as a family team seem achievable and even fun, despite the occasionally outlandish plot devices.

Inspired by The Swiss Family Robinson, creator Irwin Allen brought a twist on the Robinsonade to the small screen with Lost in Space in the 1960s: here, the Robinson family is lost again, but in space. Set in the distant future of 1997 (which seemed much more futuristic in 1965, when the series was launched), the series follows the Robinson family as they embark on a mission to colonize a distant planet to escape Earth’s overpopulation. Their ship, the Jupiter 2, is sabotaged by the scheming Dr. Zachary Smith, who accidentally strands himself along with the Robinsons in an uncharted galaxy.

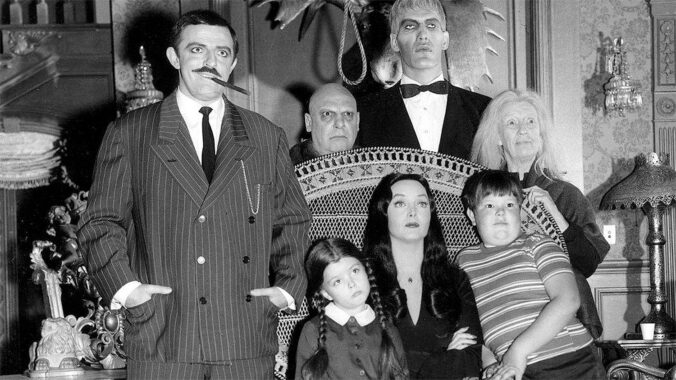

This version of Lost in Space brought us classic, campy 1960s scifi: clunky robots, cardboardy sets, and the iconic catchphrase “Danger, Will Robinson”. Dr. Smith, who began as a sinister villain, quickly morphed into a clumsy comedic character, stealing every scene with his cowardly antics. Though entertaining at times, the original Lost in Space made no effort to be realistic and relied too much on slapstick humor and “monster of the week” episodes. It was fine for its time, but it often lacked depth or continuity. However, it did spark imaginations and set the stage for the scifi family adventures to come.

In 1998 we got Lost in Space, the big-screen adaptation meant to reintroduce the Robinsons to a new generation. Starring Gary Oldman as a creepier Dr. Smith and a whole lot of CGI, this movie went full throttle with its special effects. The story largely stayed the same: the Robinson family, Dr. Smith’s betrayal, and the quest to return home. While the film had some cool moments, it also had a bit of an identity crisis. It was tonally inconsistent, wavering between scifi action and family drama, and it often got lost in its own convoluted plot twists. Despite the star-studded cast (William Hurt, Matt LeBlanc, Mimi Rogers, Heather Graham, and good old eerie Oldman), it fell flat with audiences, who were left scratching their heads over some confusing story choices (especially that poorly conceived time travel bit). It didn’t exactly do justice to the Robinsons’ legacy, unless you enjoy that kind of late-90s blockbuster energy. And that alien monkey is an unforgivably stupid idea.

And then came the 2018 Netflix reboot of Lost in Space. Finally, a version that explored the original concept with some depth and creativity. The Robinsons were once again stranded in a hostile galaxy, but this time with a serious upgrade in production, storytelling, and character depth. This series put the focus back on family dynamics, making each Robinson a fleshed-out character with distinct strengths, flaws, and personal arcs.

This Lost in Space skillfully blended high-stakes drama with visually stunning scifi worlds, bringing a modern spin to the Robinsonade. But what makes it really work is the reinvention of the main characters

John Robinson (Toby Stephens) is now a career military man. He begins the series as a somewhat distant father and husband. His years away on duty strained his relationship with his family, particularly Maureen, and left him struggling to connect with his children. However, throughout their perilous journey, John evolves into a steadfast protector and a more emotionally available father, proving his devotion to his family through acts of heroism and sacrifice. His practical mindset and combat skills are crucial in ensuring the family’s survival.

Maureen Robinson (Molly Parker), very differently from the previous versions, is now the brains behind the Robinsons’ mission to colonize space. She is a brilliant scientist, fiercely determined, resourceful, and willing to make tough decisions to ensure her family’s survival. Maureen’s love for her children is her main drive, though her single-minded focus sometimes causes friction, particularly when her ambition leads her to make morally ambiguous choices. She’s a powerful portrayal of a mother and leader in equal measure.

The Robinson sisters, who had very little agency in their previous iterations, now are strong figures with their own character arcs. Judy (Taylor Russell), the eldest, is now Maureen’s daughter from a previous relationship, adding an interesting dynamic to the family structure. A young doctor with nerves of steel, she is a natural leader and role model for her siblings. Her mixed-race heritage is a refreshing update to the character and adds a modern dimension to the family’s story. Penny (Mina Sundwall), the middle child, provides much of the series’ humor and heart. She’s sarcastic, creative, and sometimes impulsive, balancing the serious stakes of the story with her lighthearted quips and teenage perspective. She’s also, in a way, the narrator of the story.

Will Robinson (Maxwell Jenkins), boy genius, is in the center of the narrative, not so much for his personality but because of his link with the Robot. He can be an annoying character at times, especially when he combines an idealistic moral compass with the very naive and inexperieced decision making process of a child.

The Robot (Brian Steele) was completely reinvented for this series, from his looks to his origins. Now he is an alien machine with a mysterious past. Initially terrifying, he transforms into Will’s loyal guardian after an early act of compassion. The Robot’s arc explores themes of redemption and free will, as he struggles to reconcile his violent past with his new role as a family ally. His bond with Will is one of the show’s emotional pillars, offering moments of warmth and tension alike. And yes, the Robot says “Danger, Will Robinson”.

Someone decided that Don West (Ignacio Serricchio) should be the comedic character in the group, and he was demoted from the dashing pilot and adventurer of the original series to a bumbling roguish mechanic. I think he was supposed to be the lovable scoundrel with a heart of gold, but no character carrying a pet chicken can be taken seriously.

And finally, Dr. Smith (Parker Posey), the most interesting reinvention for this version of Lost in Space. Unlike the campy villain of the original series, this Dr. Smith is a cunning and dangerous sociopath, willing to exploit anyone to survive. Her backstory reveals a troubled and desperate individual who uses deception as her primary weapon. Despite her villainous tendencies, her complexity makes her a fascinating character, the kind you love to hate but can’t entirely dismiss. Her unpredictability keeps everyone on edge.

Where the original series was largely episodic, the 2018 reboot gave us a more serialized story that built real suspense and stakes, making each escape and confrontation feel genuinely perilous. The modern Lost in Space didn’t just update the effects, it also enriched the emotional layers and themes.